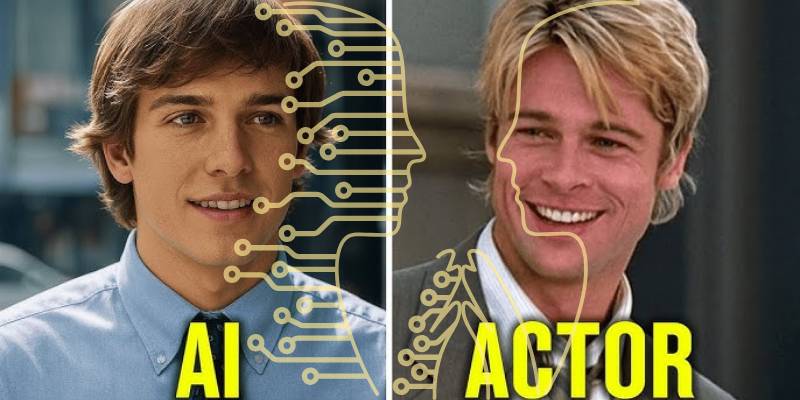

Picture this: a streaming platform releases a blockbuster movie, and its lead actor doesn’t exist. Not in the way we think of actors existing.

No human sat in a trailer waiting for makeup, no one memorized lines or wrestled with stage fright. Instead, an AI-generated performer—crafted pixel by pixel, frame by frame—delivers every line with flawless precision.

The face is photorealistic, the gestures are lifelike, and the performance feels eerily convincing.

Now comes the uncomfortable part: who owns that performance? Should it be treated the same way we treat human performances, with protections under copyright law? Or is this a category mistake, confusing machine-made output with human artistry?

That’s the messy, fascinating question I want to wrestle with today.

What Do We Mean by “Copyright and Actors”?

First, let’s clear up the basics. Traditionally, copyright and actors are two separate but related concepts.

Actors don’t own copyright over their performances (the script and the film are usually owned by studios or production companies). Instead, actors have rights through contracts, unions, and image protection.

But AI changes the equation. When the “actor” is generated entirely by software, who gets credit? Who gets protection? Is it the programmer?

The studio that paid for the training data? Or should the AI-generated likeness itself be considered a legal entity of sorts?

It sounds absurd, but remember: intellectual property law has a history of adapting to strange new frontiers.

Think about how music sampling forced courts to rethink ownership in the 1990s, or how photography raised similar questions in the 19th century.

The Economic Context

We can’t discuss this without looking at the money.

- According to PwC’s Global Entertainment & Media Outlook, the video entertainment industry will hit $915 billion by 2027.

- Deepfake and synthetic media markets alone are projected to surpass $75 billion by 2030 (MarketsandMarkets).

- Studios are already experimenting with AI doubles. Disney, for example, has invested heavily in “de-aging” technology and photorealistic CGI characters.

This isn’t hypothetical. AI-generated actors are already creeping into commercials, video games, and films. Which makes ownership issues urgent, not theoretical.

The Case For Copyright Protection

Let’s play devil’s advocate. Why might AI-generated actors deserve copyright-like protections?

- Encouraging innovation

If studios and creators know their synthetic actors can be legally protected, they’ll invest more in developing them. This mirrors the argument for copyright in general: protection encourages creativity (or, in this case, technical innovation). - Preventing misuse

Imagine you design a unique AI actor—say, a charismatic robot with a signature smirk. Without copyright protection, anyone could copy that design and flood the market. Protection could prevent dilution and exploitation. - Consistency with other digital works

We already grant copyright to computer-generated images, music, and designs—as long as a human played some role in the creation. Why should AI actors be different?

The Case Against

Now, the other side. Why shouldn’t AI actors receive copyright protection?

- No human authorship

Copyright law is built on the idea of authorship. Courts have consistently rejected works “created by non-humans”—famously in the “monkey selfie” case, where a macaque took a photo with a human’s camera. If AI actors have no consciousness or intent, why grant them rights? - Danger to human actors

If studios can protect AI actors, they may prefer them over humans, cutting labor costs. This undermines not just economics but also the dignity of human performance. - Overextension of IP law

Extending copyright too far risks giving corporations monopolies over not just art, but even “styles” of synthetic humans. That’s a slippery slope.

The Moral Dilemmas

Here’s where it gets knotty. Even if the law says “no” today, the moral terrain is shifting.

- Authenticity: Do audiences deserve to know when an actor is synthetic?

- Consent: If an AI actor is trained on real human data (faces, voices, gestures), do those people deserve compensation?

- Legacy: Should families of deceased actors be able to block studios from using AI doubles indefinitely?

These aren’t just abstract hypotheticals. During the 2023 SAG-AFTRA strikes, one of the sticking points was studios wanting the right to scan background actors and use their likeness “for eternity” with little or no compensation. That’s not sci-fi—it’s happening now.

This brings me back to the core of moral dilemmas: AI blurs the line between tribute, theft, and innovation.

Ownership Issues in Practice

Let’s say a studio creates an AI actor named “Ava,” who stars in a blockbuster film. Who owns Ava?

- The studio? They financed her creation.

- The developers? They built the algorithms.

- The dataset providers? If Ava’s movements come from motion capture of real performers, don’t they deserve credit?

- The audience? Okay, maybe not legally—but if Ava only exists because she resonates with fans, what role does cultural ownership play?

These ownership issues could lead to endless lawsuits, unless laws evolve.

Trust and the Question of Trustworthiness

Another layer is public trust.

Audiences already wrestle with the trustworthiness of media. Deepfakes erode confidence in what we see. If AI-generated actors flood the market, will we stop believing in performances altogether?

It’s not just about entertainment. Consider politics: what if an AI-generated “actor” is used in campaign ads, playing a role that manipulates voters? Regulation becomes about more than art—it’s about democracy itself.

Global Perspectives

Different countries are approaching this differently.

- United States: The Copyright Office currently denies protection for works without human authorship.

- China: Recently issued guidelines requiring disclosure when synthetic media is used, though enforcement remains unclear.

- EU: The proposed AI Act includes rules about transparency but hasn’t resolved copyright questions yet.

The patchwork nature of regulation could create chaos. What’s copyrighted in one jurisdiction might be free game in another.

A Historical Parallel

This isn’t the first time art and technology collided. When photography emerged, painters worried their craft was obsolete.

When recorded music took off, live musicians feared replacement. Each time, the law scrambled to adapt, usually striking a balance between protecting new forms and preserving old ones.

We may be at that same turning point with AI actors.

My Personal Opinion

Here’s where I land.

AI-generated actors should not receive copyright protection as independent entities. They are tools, not creators.

Protecting them directly risks undermining human artistry and granting corporations dangerous monopolies.

However—there should be protections for the designs and likenesses of these actors, much like trademarks.

That way, studios can safeguard unique characters without elevating machines to the status of artists.

And above all, transparency should be mandatory. Audiences deserve to know if the tear on screen came from a real human or a calculated pixel pattern.

What the Future Might Hold

Looking forward, I suspect we’ll see hybrid approaches:

- Trademarks for AI actor designs.

- Contracts governing use of human likeness data in training.

- Mandatory disclosure when synthetic actors are used.

- International frameworks to avoid chaos across borders.

Will this satisfy everyone? Not likely. But it might strike a balance between innovation and ethics.

Closing Reflection

So, should AI-generated actors receive copyright protection?

My answer: no, not in the same way humans do. But yes, in carefully limited ways that protect investments without undermining the irreplaceable role of human performers.

Because at the end of the day, film isn’t just about pixels or patents—it’s about empathy. And empathy, as far as I can tell, still belongs to us.

Final Note

This debate won’t end here. It will unfold in courtrooms, studios, and living rooms over the next decade.

And every time we watch a performance, whether human or synthetic, we’ll be reminded that the question of “who owns this moment?” is not just legal—it’s profoundly human.